Empirically Analyzing the "Five Percent Rule of Materiality" in Financial Reporting Decisions

This study analyzes a sample of financial restatements from 2011 and 2012 as a way to assess a proposed “five percent rule of materiality” for financial reporting decisions. Such a rule claims the average investor is only influenced by income restatements greater than five percent. Market reactions are observed through stock price, volume, and bid-ask spread following the restatement in the Form 10-K/A. The study finds only some firms restating net income by more than five percent experience statistically significant reactions in two of these metrics. The study also suggests percent change in net income is a significant driver of percent change in the three metrics via a regression analysis. This study uses publicly available information and can only examine firms where an auditor has already determined that the restatement was material. There is no examination of firms where an auditor determined that it was immaterial and did not issue a restatement. The “five percent rule of materiality” explains a lot of what is observed in earnings restatements. As this is an area of much debate among practitioners, regulators and academics need to provide better guidance about the determination of materiality.

I. INTRODUCTION

This study examines financial restatements as a basis for exploring the concept of materiality. The project evaluates the appropriateness of the “five percent rule of materiality,” a decision-making tool which assumes the rational, average investor is only influenced by variations in reported net income greater than five percent (Vorhies, 2005). To test whether this rule holds, the study examines market reactions from a sample of five companies. These companies are selected from all restatements occurring between 2011 and 2012 which contain common characteristics of 4.02 non-reliance and revenue recognition as the driver for the restatement.

To test the five percent rule, market reactions are observed following the release of the Form 10-K/A through three metrics: stock price, volume, and bid-ask spread. A statistical test of means yields significant reactions in stock price and volume for three of four companies restating net income by an amount more than five percent. The final firm in the sample, which restates net income by less than one percent, produces no significant reaction in these variables. No firms in the sample create a significant reaction in the bid-ask spread variable. Consequently, this suggests such a five percent rule is not appropriate in determining materiality thresholds for financial reporting. Similarly, regression analysis suggests that percent change in net income is a statistically significant independent variable in determining the magnitude of the reaction in each metric.

II. BACKGROUND

Historical Background

Financial reporting seeks to provide relevant, reliable, comparable, and consistent information to investors and creditors so they may analyze performance and project cash flows to the enterprise (Financial Accounting Standards Board, 2010). The complex organizations that participate in this reporting need to determine the information necessary for its investors and creditors to evaluate performance and forecast cash flows. This problem is one of materiality. In accounting, information is considered material if, based on its nature, magnitude, or both, it would influence the decisions of financial statement users (Financial Accounting Standards Board, 2010).

Over time, management began to develop ad hoc tools for quickly assessing this question of materiality. Soon, the benchmark for materiality became fixated on fluctuations greater than five percent, particularly with regard to net income (Vorhies, 2005). After some “frustration that had built up over the years” (Barlas et al 1999) regarding an apparent reliance on similar rules of thumb, the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) issued Staff Accounting Bulletin (SAB) No. 99 – Materiality, in August 1999. In this publication, the SEC urges managers and auditors to recall that, when determining materiality, strict reliance on “any percentage or numerical threshold has no basis in the accounting literature or the law” (U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission, 1999). Future research would conclude that, in general, financial statement users carry a lower materiality threshold than do preparers and auditors (Messier, et al 2005), further perpetuating the desire of a distinct threshold for practical purposes.

Scholarly Context

The Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB) supported SAB 99 in its 2010 amended publishing of Concept Statement No. 8. The FASB writes, “The Board [FASB] cannot specify a uniform quantitative threshold for materiality or predetermine what could be material in a particular situation” (Financial Accounting Standards Board, 2010).

Following accounting scandals from the early 2000s and subsequent passage of the Sarbanes-Oxley Act in 2002, accurate identification and disclosure of material information resurfaced as a key issue facing the accounting profession. Nearly six years after the release of SAB 99, James Vorhies, CPA, published an article in the May 2005 Journal of Accountancy titled “The New Importance of Materiality.” This piece highlights the importance of materiality in management’s efforts to comply with Sarbanes-Oxley requirements for reporting on risk and internal control. Vorhies chronicles accountants’ use of the five percent rule and grounded it as a “fundamental basis for materiality estimates” (2005). He also echoes the SEC’s 1999 message in SAB 99 by noting the inappropriateness of relying on a numeral target in determining materiality and stressing the use of qualitative factors. He claims the problem lies in the analysis of qualitative factors because of their complexity and immeasurability; therefore, he states professionals still rely on quantitative elements in identifying potentially material information (Vorhies, 2005).

Vorhies’ discussion sparked a spirited response in the Journal of Accountancy’s August 2005 issue from Steven Johnson, CPA. Johnson worries Vorhies’ language implies an authoritative five percent rule and would leave readers believing misstatements less than five percent do not affect a company’s overall financial presentation. He consequently argues its use in practice as an internal starting point only and not truly a “rule” (Johnson, 2005).

A study at New York University seeks to address both quantitative and qualitative characteristics of financial restatements and their short-term market reactions. Research concludes stock prices are negatively related to the restatement’s magnitude; the higher the restatement amount, the greater negative market reaction. Similarly, stock prices tend to react more significantly when the nature of the restatement is either fraud or revenue recognition (Wu, 2002). Wu’s findings that fraud and revenue recognition restatements cause the largest reactions are also supported by research at the University of Kansas (Scholz, 2008).

Researchers at the University Valahia of Targoviste in Romania expand on previous critiques of the five percent rule by placing it in context with the purpose of financial reporting. While past authors condemned the rule as inadequate because of its emphasis on quantitative factors only, these researchers rehash the old arguments and further claim that it fails to aid investors and creditors in their analysis of company’s financial data (Cucui et al., 2010). These same researchers also argue against the use of a five percent benchmark and, like regulators, emphasize the users of financial data and promote a materiality definition that is rooted in altering their decision making process (Cucui et al., 2010). This serves as support to the SEC and FASB position further by emphasizing the core purpose of financial reporting.

Study Foundation

The idea to analyze the five percent rule sprouted from the examination of a restatement by JetBlue Airways in February 2011. The restatement resulted in a positive increase in 2009 net income by just over five percent. To understand more completely the implication of the five percent rule beyond this singular application, it was determined to expand the sample size by finding other financial restatements which mimic the characteristics found in the JetBlue restatement announcement. These characteristics include the following:

- 4.02 non-reliance on previously issued financial statement

- Revenue recognition as the driving force for restatement

- Restatement filed in 2011-2012

Academic Contribution

Previous work on the five percent materiality rule indicates an overall opposition because of a non-reliance on qualitative factors, much like the SEC and FASB statements. Others attempt to identify those qualitative factors by developing useful profiles of companies that can expect negative reactions based on the type and magnitude of financial restatement. This study will add to the existing body of knowledge by statistically analyzing the five percent rule as a starting point for understanding materiality in financial reporting.

III. HYPOTHESES

Materiality is at least a twofold concept containing both qualitative and quantitative factors. This study looks for support for a quantitative effect and the sample is selected to isolate the effect. First, all revenue restatements are selected because prior research has shown that investors find revenue restatements material (Wu, 2002). Without this criteria, it would be impossible for us to find any restatements that fall below 5% if the 5% rule holds in practice. Put another way, if an auditor discovered an error but judged it not to be material because it was less than 5% there would not be an 8-K or an investor reaction to study. Secondly, the 8-K announcement needed to include the language of a revenue restatement but not include any quantitative numbers. This enabled us to separate the reaction to the revenue restatement (qualitative) and the reaction to the magnitude (qualitative).Finally, the 10-K/A was the first disclosure of the numbers necessary to identify the magnitude of the restatement.

For those restatements in this sample, all percent changes in net income are disclosed in the Form 10-K/A rather than the Form 8-K. It is expected that the market reacts significantly following the Form 8-K because this is the form that categorizes the restatement as one of revenue recognition which, prior research shows, engenders a significant market reaction (Wu, 2002). Subsequently, it is anticipated that any significant reaction following the Form 10-K/A is due to the magnitude of the net income restatement; therefore, the Form 10-K/A date serves as the central date in the study’s analysis. The construction of the sample consequently is designed to attempt to isolate the reaction due to revenue recognition (around the Form 8-K) from the reaction due to the magnitude of the income restatement (around the Form 10-K/A) so as to assess the five percent rule more accurately.

Furthermore, a positive relationship is expected between the magnitude of the net income restatement and the magnitude of the market reaction (around the Form 10-K/A). To assess these expectations, six testable hypotheses are developed below, two for each metric, from which to draw final commentary regarding materiality.

Stock Price

Stock price is an indicator of the investing public’s perceived value of a company. With devaluation of a company comes a desire to sell, increasing supply of the stock in the market. Economics explains that, other things equal, increased supply drives down prices. Based on this, the following are proposed:

- H1A: For restatements with 4.02 non-reliance and revenue recognition citations without quantitative data disclosure, the stock price will decline significantly around the issuance of the 10-K/A for restatements above and below 5% of net income.

- H1B: Following the 10-K/A disclosure, a greater stock price decrease will not be associated with a larger magnitude of the restatement.

H1A pertains to the market reaction to the magnitude of the restatement. All companies have previously issued an 8-K outlining the need for a restatement related to revenue but not disclosing the magnitude. The hypothesis is stated in null form in accordance with SEC and other authoritative bodies that materiality is not based on a quantitative criteria. However if we find evidence that there is no significant reaction for companies below 5% (absolute value) but a there is one for those above 5% (below -5%), it supports a more practitioner based theory that small restatements are not of interested to investors. H1B is also stated in null and speaks to the spirit of the 5% rule or a graduated materiality. A positive significant reaction suggests that the greater the magnitude the greater the materiality. We expect this to hold in both the positive and negative quadrants.

Volume

Volume is an indicator of an investor’s willingness to hold on to a stock. Accordingly, it is expected that volume reacts more severely when restatements are larger than five percent. Consequently, the following are anticipated:

- H2A: For restatements with 4.02 non-reliance and revenue recognition citations, the volume will increase significantly around the issuance of the 10-K/A for restatements above and below 5% of net income.

- H2B: Following the 10-K/A disclosure, the magnitude of the volume increase will be positively associated with the magnitude of the restatement.

H2A tests materiality by way of the investor’s willingness to hold. A material disclosure should result in a change in the willingness to hold of investors. Some investors will be more willing to hold, others less and this changes creates more transaction volume between investors. The hypothesis is stated in null, consistent with the SEC assertions that materiality is not based on a quantitative criteria. The 5% materiality rule suggests that only those with restatements greater than 5% (absolute value) of net income will get a significant change in volume. Restatements below that will not change the willingness to hold of investors. H2B is stated in null and speaks to the graduated materiality based on magnitude. The magnitude of the restatement is test in absolute value terms because a either large positive or negative reaction could change an investor’s willingness to hold. Regardless of whether willingness to hold increases or decreases, the result is an increase in volume. A significant positive relationship suggests that the larger the restatement the greater the change in investor’s willingness to hold the stock.

Bid-Ask Spread

The bid-ask spread represents the difference between the price a market maker or clearing house is willing to pay for a security (bid) and the price at which a it wants to sell that security (ask). The bid-ask spread also indicates a stock’s volatility or risk. The more risky or volatile the security, the more profit is demanded by the market maker to hold the stock. Accordingly, larger bid-ask spreads are expected for larger percentage restatements in net income surrounding the 10-K/A disclosure.

- H3A: For restatements with 4.02 non-reliance and revenue recognition citations, the bid-ask spread will increase significantly around the issuance of the 10-K/A for restatements above and below 5% of net income.

- H3B: Following the 10-K/A disclosure, the magnitude of the bid-ask spread increase will be positively associated with the magnitude of the restatement.

A material restatement could change the perception of risk of a company. H3A is stated in null consistent with the SEC’s assertions that materiality is not based on quantitative criteria. Significant changes in bid-ask spread, suggest changes in risk perceptions and if we find evidence of this for restatements above 5% (absolute value) of net income and not below then we find support for the practitioner’s theory that 5% is material through changes in the risk perception. H3B is stated in null and speaks to the idea of graduated materiality. A positive significant reaction suggests that the larger the restatement as a % of net income the greater the change in the risk perception as measured through the bid-ask spread.

IV. METHODOLOGY

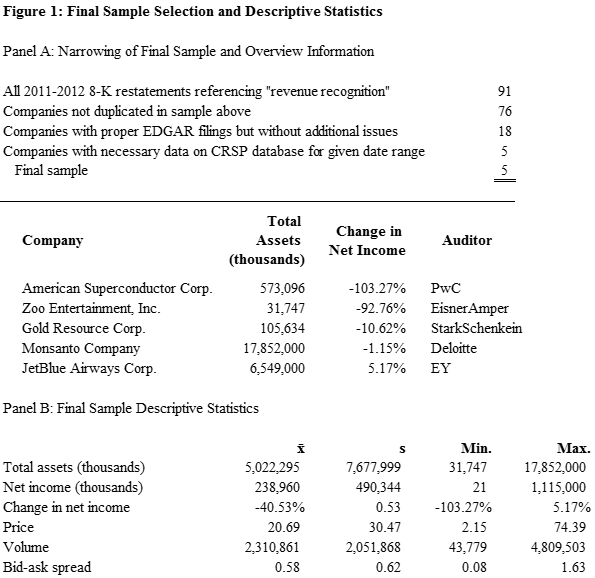

The progression of the sampling procedure to the final sample used in this study, as well as basic overview information for those firms, can be found in Figure 1 Panel A.

Figure 1 Panel B provides additional overview information for the entire final sample as a collective. The descriptive statistics shown are based on the ten days prior to the criteria disclosure date and the three days following the criteria disclosure date. The ten-day-prior window establishes a baseline for comparison while the three-day-after window is designed to capture market reactions, assuming a semi-strong market (Fama, 1970).

As outlined, there are two hypotheses to be tested for each metric: stock price, volume, and bid-ask spread. The first of these hypotheses deals with the significance of changes in those metrics before and after the 10-K/A disclosure. To analyze this significance, net income data are pulled from the original Form 10-K as well as Form 10-K/A for each company to calculate the percentage change. Historical price, volume, and bid-ask data are drawn from the Center for Research in Securities Prices (CRSP) database. The data are then used to perform a test of means for each metric to gauge the significance of changes in those metrics before and after the 10-K/A disclosure.

Like the aggregate sample data provided in Figure 1, the test of means data – found in Figure 2 – calculates the baseline average over a ten day interval while the reaction window is calculated over a three day period. Three days is used for the reaction window because of the assumption of a semi-strong market in which the market internalizes information less than instantaneously (Fama, 1970). The p-values are calculated using Welch’s adjusted degrees of freedom assuming unequal variances between the ten-day-prior interval and the three-day-after window (Doane & Seward, 2010).

The second hypothesis for each metric revolves around the relationship between the magnitude of the percentage change in income and the magnitude of the observed movement in the metric. To test this, all firms are combined and three separate regressions are run with percentage change in net income as the independent variable and percentage change in each individual metric as the dependent variable. For the volume and bid-ask spread regressions, the absolute values of the percentage changes in net income are used. This is done because the analysis is focused on magnitude of the restatement, not direction. However, the magnitude of price is direction-dependent, so the percentage change in income used in that regression could be both positive and negative.

Two sets of regressions are included, one with an “outlier” and one without it. This potential outlier is American Superconductor. The company was identified as a potential outlier because it is the only company whose percentage change in net income is greater than one standard deviation away from the sample average (see Figure 1). Due to the small sample size, this potential outlier was not calculated using the inner quartile range (Doane & Seward, 2010); therefore, the results of both regressions are included for each metric in Figure 3 to facilitate full disclosure. Similarly, the percentage change in net income is calculated slightly differently for American Superconductor than the other selections because it results in a restatement across three quarters, not one full year. The change in income is subsequently based on a nine-month cumulative effect.

V. RESULTS

This section presents the study’s results and revisits each of the six hypotheses previously developed to analyze them in the context of the five percent rule for materiality.

Significance of Market Reactions – Tests of Means

Results for the significance of market reactions captured in each of the three metrics via the test of means can be found in Figure 2.

- H1A: For restatements with 4.02 non-reliance and revenue recognition citations, the stock price will react significantly to the information.

As shown in Panel A on Figure 2, at an alpha level of .05, three of the five firms in this sample generate a significant stock price reaction around the Form 10-K/A. Consistent with the five percent rule, these three firms restate net income by more than five percent. Of particular interest is JetBlue Airways, whose net income restatement is just over five percent, because its p-value is similarly just lower than .05. This suggests a critical point in which percentage change and reaction significance converge, consistent with the five percent rule. Put simply, the percent change in income is barely over five percent, and its stock price reaction is barely statistically significant.

The predictive power of the five percent rule does not apply in the example of Zoo Entertainment. This firm restates net income by well over five percent, yet the stock price reaction is not significant even at a .10 alpha level. It should be noted that, although the Form 10-K/A discloses the true restatement amount, the information contained in its Form 8-K complicates the analysis. This form includes a schedule of estimated re-casted financial statements given the 4.02 non-reliance. This data proved to be incorrect and the more accurate financial impact was actually released in the Form 10-K/A. Despite this information, the Form 10-K/A is still used in the analysis because it would be impossible to distinguish whether any observed reaction around the Form 8-K resulted from the type of restatement (revenue recognition), which research has already shown to be a significant factor in market reaction (Wu, 2002), or from the percent change restatement.

The final firm, Monsanto Company, yields the most insignificant stock price reaction and is the only selection with a net income restatement below five percent. This occurrence is consistent with the five percent rule. Overall, logic of the five percent rule applies to four of five companies in this sample.

- H2A: For restatements with 4.02 non-reliance and revenue recognition citations, volume will increase significantly.

The data on Panel B of Figure 2 can be used to address the question of significance in volume reactions. Of the five firms in the sample, only two of them generate significant volume reactions at a .05 alpha level; a third is added to this group when analyzed at a .10 alpha level. These are the same three firms found to produce a significant stock price reaction in Panel A. Again, Zoo Entertainment seems to be an exception to the five percent rule with an income restatement well above five percent but an insignificant volume reaction. Monsanto Company, the selection with an income restatement less than five percent, generates a high p-value on this metric, suggesting statistical insignificance. This is also consistent with the five percent rule in that such a low income restatement should engender an insignificant market response. As with the previous metric, the rule seems to apply to only four of five firms in the sample.

- H3A: For restatements with 4.02 non-reliance and revenue recognition citations, the bid-ask spread will increase significantly.

As shown in Panel C of Figure 2, none of the firms create a significant bid-ask spread reaction following the Form 10-K/A release at a .05 alpha level. Only one reaction becomes statistically significant at a .10 level. Monsanto Company, however, still produces the most insignificant reaction of all five firms. Overall, the five percent rule does not seem to apply to any firms in the sample when bid-ask spread is used as a metric for capturing investor reaction. The lack of a significant reaction in the bid-ask spread could result from the five percent rule’s emphasis on average investors. The spread is determined by market makers and institutions that act between individuals and the market. The average investor, however, may not interact through these intermediaries or may participate through relatively tangential intermediaries; therefore, their impact and decision making may not be captured adequately in this metric (Hollifield et al, 2011).

Magnitude of Market Reactions – Regression Analysis

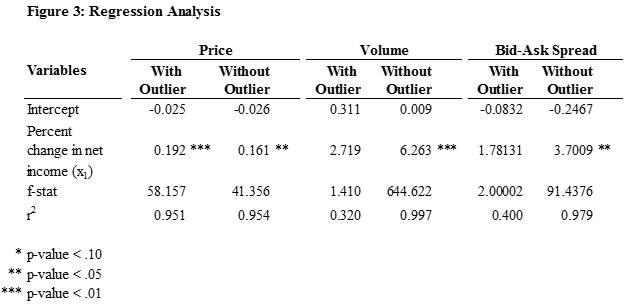

The regression coefficients, drawn from regressions running percent change in net income against percent change in the given metrics, are in Figure 3.

Both regressions, with and without the potential outlier, yield a significant independent variable for the stock price metric assuming a .05 alpha level. The independent variables for volume and bid-ask spread, however, are only significant at a .05 level when the potential outlier is omitted.

- H1B: Following the 10-K/A disclosure, a greater stock price decrease will be associated with a larger magnitude of the restatement.

As shown in Figure 3, percent change in net income acts as a significant independent variable at a .05 alpha level when percent change in price is the dependent variable, both with and without the potential outlier. Both regressions yield strong coefficients of determination (r2), suggesting high predictive value. Similarly, the intercept in both regressions are close to zero, meaning no change in net income should cause little to no change in price. This model makes economic sense and lends merit to the foundation of the five percent rule: the idea that higher percent changes in income drive increased market reactions.

- H2B: Following the 10-K/A disclosure, the magnitude of the volume increase will be positively associated with the magnitude of the restatement.

Referring to Figure 3, percent change in income is a significant independent variable at a .01 level, with percent change in volume as the dependent variable, when the potential outlier is omitted from the sample. Similarly, the intercept falls much closer to zero without the outlier, making more economic sense because a zero percent change in net income should not produce an increase in volume when other things are equal. Furthermore, the coefficient of determination greatly increases when the model excludes the outlier, suggesting a better fit and higher predictive value.

- H3B: Following the 10-K/A disclosure, the magnitude of the bid-ask spread increase will be positively associated with the magnitude of the restatement.

The final columns in Figure 3 show regression data when percent change in bid-ask spread is the dependent variable in the analysis. With the outlier omitted, the significance of percent change in net income as the independent variable greatly increases. Similarly, the coefficient of determination more than doubles from the regression that included the potential outlier, once again suggesting a better goodness of fit and a higher predictive value for the model overall. Without the potential outlier, the intercept actually moves farther away from zero, which is not typically expected given the variables at play.

VI. CONCLUSION AND LIMITATIONS

The first three hypotheses (H1A, H2A, and H3A) seek to examine the five percent rule directly by measuring market reactions to net income changes firsthand. Of the five selections in the sample, the “rule” seems to apply to all of them except Zoo Entertainment when examining changes in stock price and volume. Of those four, the three firms restating income by more than five percent experience statistically significant changes in stock price and volume. The fourth firm, which restates income by less than five percent, yields the most statistically insignificant changes in stock price and volume. The rule does not seem to apply to the final firm, Zoo Entertainment, despite its change in net income beyond five percent. The fact that the rule fits only four of five firms lends credit to the SEC and other regulatory authorities that have spoken out against the use of a hard-and-fast quantitative materiality rule that can be applied to all financial restatements.

Although the singular exception of Zoo Entertainment discredits the five percent rule after analyzing the stock price and volume, one would still expect a similar reaction for bid-ask spread even if not perfectly in line with the rule. The potential for a lack of average investor contribution to the bid-ask spread metric could help explain the total lack of significant reaction around the variable.

The second set of hypotheses (H1B, H2B, and H3B) revolves around the magnitude of the net income restatement as a driver of the magnitude of change in the given metrics. This can be thought of as the logical foundation for the five percent rule; that is, investors will react less significantly to smaller income restatements and will react to larger income restatements more significantly. The subsequent regression analysis used to test this logical foundation suggests that, with the potential outlier excluded, percent change in net income is a significant independent variable in predicting the percent change in each metric. This, broadly speaking, proposes a significant relationship between net income and the chosen metrics. This contribution, however, is much more general in nature than the former analysis. It does not seek to examine the five percent rule directly, but rather the underlying economic reasoning behind the rule.

A synthesis of these conclusions yields a larger conclusion about this study as a whole. The goal is to assess the five percent rule as a proposed materiality standard. The statistical test of means and subsequent results in Figure 2 show that the rule is not an authoritative principle in all applications. The singular exception of Zoo Entertainment attests to this. This rule, however, does retain logical support in its economic underpinnings. The latter analysis and results, found in Figure 3, establish a fairly strong direct relationship between percent change in net income and percent change in various metrics.

Given these conclusions, several recommendations can be ascertained as to best practices when dealing with materiality. Firstly, this study’s regression analysis suggests that firms should expect greater market reactions as restatements in income increase. This, however, should not influence the actual decision in determining what is or is not material for disclosure purposes. Similarly, five percent has proven not to be an all-encompassing benchmark for materiality. As the authoritative literature claims, materiality stretches beyond quantitative factors. Investors may find income restatements less than five percent to be material and, conversely, may find restatements greater than five percent to be immaterial, as is the case in the example of Zoo Entertainment. Despite access to perfectly rational financial data, investors can still act irrationally and are equally influenced by quantitative factors like government policy or perceived risk trends (Alnajjar, 2013). Nonetheless, five percent may serve decision-makers as a useful starting point for assessing the severity of market reactions.

This study does support the five percent rule as it is articulated in a literal sense. In this sample, investors were indeed only influenced by fluctuations in income greater than five percent. However, the rule’s essence is its use as a tool for delineating the material from the immaterial. When analyzed in this light, it is clear that the rule fails to separate material and immaterial reactions simply based on the percent change in income. Because of this occurrence, the rule is not recommended for use as a guide in determining materiality for financial reporting. It does, however, lend insights to predicting investor reactions. In general, most selections in this study’s sample tend to react significantly to restatements more than five percent. Even though this is not authoritative for external use, management can find value in this knowledge by using it to plan courses of action to counter potential investor responses.

Limitations

Despite this study’s recommendations and conclusions, some limitations must be discussed. The most obvious limitation is the small sample size. As Figure 1 portrays, the original intent was to include a large sample of firms in the analysis. Due to various issues in data collection and reporting, the sample quickly dwindled down to five firms given the other quantitative criteria.

Within this sample, only one company restated net income by less than five percent. A greater number of firms with smaller restatements in net income would have aided the analysis by trying to identify material reactions for relatively small restatements. Conclusions reached regarding the rule, as written, would be stronger if such data had been available. However, if the five percent rule is indeed being used in practice, such a phenomenon would be expected. If auditors and decision-makers deem net income restatements less than five percent to be immaterial, such sample selections would be unattainable for testing.

Similarly, this study does not take into account other factors that could influence the metrics at the time of the criteria disclosure. As such, the regression analysis is a simple regression assuming one independent variable. Prior research shows investors can be influenced by qualitative information; however, they are not included in the regression analyses. Instead, the regressions were kept simple to establish relationships between variables more clearly.

Finally, one selection in this sample, American Superconductor, released early yet inaccurate estimates in its Form 8-K. This partially contaminates its true disclosure date as partial information was released before the Form 10-K/A. Consequently, market reactions may have already occurred around the Form 8-K; however, measuring around this form would prove difficult in analyzing as the reaction could be due to its percentage change in income or its type as a revenue recognition restatement. Nonetheless, the market did not receive restatement data for the first time on the day of the Form 10-K/A, which could have impacted the values of the data collected.

Authors

Adam Morgan

PricewaterhouseCoopers LLP

Assurance Associate

Mariah Webinger, PhD

John Carroll University

Department of Accountancy

[email protected]

216-397-4225

20700 North Park Blvd

University Heights, OH 44118

Works Cited

Alnajjar, M., (2013). Investor Based Psychological Decision Making Model. Far East Journal of Psychology and Business, June, Volume 11, pp. 47-56.

American Superconductor Corporation, July 11, 2011. Form 8-K, Washington, D.C.: U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission.

American Superconductor Corporation, September 23, 2011. Form 10-K/A, Washington, D.C.: U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission.

Barlas, S. et al., (1999). SEC on 5% Materiality Rule. Strategic Finance, October, 81(4), pp. 29-77.

Cucui, I., Munteanu, V., Niculescu, M. & Zuca, M., (2010). Audit Risk, Materiality and the Professional Judgment of the Auditor. Recent Advances in Business Administration, pp. 78-82.

Doane, D. P. & Seward, L. E., (2010). Essential Statistics in Business & Economics. New York, New York: McGraw-Hill.

Fama, E. F., (1970). Efficient Capital Markets: A Review of Theory and Empirical Work. Journal of Finance, 25(2), pp. 383-417.

Financial Accounting Standards Board, (2010). Statement of Financial Accounting Concepts No. 8, Norwalk: Financial Accounting Foundation.

Gold Resource Corporation, November 8, (2011). Form 8-K, Washington, D.C.: U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission.

Hollifield, B., Neklyudow, A. & Spatt, C., (2011). Bid-Ask Spreads and the Pricing of Securitizations: 144a vs. Registered Securitizations”, s.l.: Tepper School of Business, Carnegie Mellon University.

JetBlue Corporation, February 7, 2011. Form 10K/A, Washington, D.C.: U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission.

JetBlue Corporation, January 18, 2011. Form 8-K, Washington, D.C.: U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission.

Johnson, S. D., (2005). The 5% Rule of Materiality. Journal of Accountancy.

Messier, W. J., Martinov-Bennie, N. & Eilifsen, A., (2005). A Review and Integration of Empirical Research on Materiality: Two Decades Later. Auditing: A Journal of Practice and Theory, 24(2).

Monsanto Company, October 11, 2011. Form 8-K, Washington, D.C.: U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission.

Monsanto Company, October 27, 2011. Form 10-K/A, Washington, D.C.: U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission.

Scholz, S., (2008). The Changing Nature and Consequences of Public Company Financial Restatements, s.l.: U.S. Department of the Treasury.

U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission, (1999). SEC Staff Accounting Bulletin: No. 99 – Materiality. [Online]

Vorhies, J. B., (2005). The New Importance of Materiality. Journal of Accountancy, May.

Wu, M., 2002. Earnings Restatements: A Capital Market Perspective, s.l.: New York University.

Zoo Entertainment Inc., April 15, 2011. Form 8-K, Washington, D.C.: U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission.

Zoo Entertainment Inc., May 16, 2011. Form 10-K/A, Washington, D.C.: U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission.